Allam948736 (talk | contribs) (Fixed incorrect description in the first digits section) Tag: Visual edit |

m (clarification of the current status) |

||

| (31 intermediate revisions by 8 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | '''Tetration''', also known as '''hyper4''', '''superpower''', '''superexponentiation''', '''superdegree''', '''powerlog''', or '''power tower''',<ref>Robert Munafo, [http://mrob.com/pub/math/largenum-3.html#hyper4 Beyond Exponents: the hyper4 Operator]. ''Large Numbers''.</ref> is a binary mathematical operator (that is to say, one with just two inputs), defined as \(^yx = x^{x^{x^{ |

+ | '''Tetration''', also known as '''hyper4''', '''superpower''', '''superexponentiation''', '''superdegree''', '''powerlog''', or '''power tower''',<ref>Robert Munafo, [http://mrob.com/pub/math/largenum-3.html#hyper4 Beyond Exponents: the hyper4 Operator]. ''Large Numbers''.</ref> is a binary mathematical operator (that is to say, one with just two inputs), defined as \(^yx = x^{x^{x^{\cdot^{\cdot^{\cdot}}}}}\) with \(y\) copies of \(x\). In other words, tetration is repeated [[exponentiation]]. Formally, this is |

\[^0x=1\] |

\[^0x=1\] |

||

| Line 39: | Line 39: | ||

* In [[arrow notation]] it is \(x \uparrow\uparrow y\), nowadays the most common way to denote tetration. |

* In [[arrow notation]] it is \(x \uparrow\uparrow y\), nowadays the most common way to denote tetration. |

||

* In [[chained arrow notation]] it is \(x \rightarrow y \rightarrow 2\). |

* In [[chained arrow notation]] it is \(x \rightarrow y \rightarrow 2\). |

||

| − | * In [[array notation]] it is \(\{x, y, 2\}\) |

+ | * In [[array notation|BEAF]] it is \(\{x, y, 2\}\)<ref>[http://polytope.net/hedrondude/array.htm Exploding Array Function]</ref>. |

** The latter of these also represents tetration in [[X-Sequence Hyper-Exponential Notation]]. |

** The latter of these also represents tetration in [[X-Sequence Hyper-Exponential Notation]]. |

||

| + | * Using Bowers's extended operators, it is \(x\ \{2\}\ y\). |

||

* In [[Hyper-E notation]] it is E[x]1#y (alternatively x^1#y). |

* In [[Hyper-E notation]] it is E[x]1#y (alternatively x^1#y). |

||

* In plus notation it is \(x ++++ y\). |

* In plus notation it is \(x ++++ y\). |

||

| Line 48: | Line 49: | ||

== Properties == |

== Properties == |

||

| − | Tetration lacks many of the symmetrical properties of the lower hyper- |

+ | Tetration lacks many of the symmetrical properties of the lower [[hyper-operator]]s, so it is difficult to manipulate algebraically. However, it does have a few noteworthy properties of its own. |

=== Power identity === |

=== Power identity === |

||

| Line 96: | Line 97: | ||

# If \(y \geq y_0\), then \(\textrm{Rep}(^yx) = \textrm{Rep}(x^{\textrm{Rep}(^{y-1}x)}+b^d)\). |

# If \(y \geq y_0\), then \(\textrm{Rep}(^yx) = \textrm{Rep}(x^{\textrm{Rep}(^{y-1}x)}+b^d)\). |

||

In particular, the last \(d\) digit of \(^yx\) in base \(b\) can be computed as \(\textrm{Rep}(^yx) \mod{b^d}\) because \((^yx - \textrm{Red}(^yx)) \mod{b^d} = 0\). |

In particular, the last \(d\) digit of \(^yx\) in base \(b\) can be computed as \(\textrm{Rep}(^yx) \mod{b^d}\) because \((^yx - \textrm{Red}(^yx)) \mod{b^d} = 0\). |

||

| + | |||

| + | There was another '''wrong''' method to compute the last digits of [[Graham's number]], which was believed to be correct without any reason in this community. Due to the method, for any natural number \(d\), the last \(d\) digits \(D(d)\) of Graham's number in base \(10\) could be computed in the following recursive way: |

||

| + | \begin{eqnarray*} |

||

| + | D(d) & = & \left\{ \begin{array}{ll} 3 & (d = 0) \\ 3^{N(d-1)} \text{ mod } 10^d & (d > 0) \end{array} \right. |

||

| + | \end{eqnarray*} |

||

| + | Note that the recursion starts from \(d = 0\), but the result of \(D(0)\) is not meaningful because "the last \(0\) digit" of Graham's number does not make sense. For the obvious reason why this method is wrong, see the main article on [[Graham's number#Calculating_last_digits|Graham's number]]. |

||

| + | |||

| + | It can be quite easily justified by modifying the upperbound of the length \(d\) of the digits. Let \(b\), \(x\), and \(y\) be positive integers such that \(b\) is coprime to \(x\). We define a natural number \(D_b(x,y)\) in the following recursive way: |

||

| + | \begin{eqnarray*} |

||

| + | D_b(x,y) & = & \left\{ \begin{array}{ll} x^x \text{ mod } b & (y = 1) \\ x^{D_b(x,y-1)} \text{ mod } b^y & (y > 1) \end{array} \right. |

||

| + | \end{eqnarray*} |

||

| + | We have \(D_{10}(3,y) = D(y)\) for any positive integer \(y\), and hence this is an extension of the unary \(D\) function above. It is natural to ask when \(D_b(x,d)\) coincides with the last \(d\) digits of \({}^y x\) for positive integers \(d\) and \(y\). The wrong method was based on the wrong assumption that \(D_{10}(3,d)\) coincides with the last \(d\) digits of Graham's number for '''any''' positive integer \(d\). |

||

| + | |||

| + | Assume that there exists a pair \((d_0,y_0)\) of positive integers such that for \(b^{d_0}\) is divisible by the least common divisor of \(\phi(p^{d_0+1})\) for all prime factors \(p\) of \(b\) and \(D_b(x,d_0)\) coincides with the last \(d_0\) digits of \({}^{y_0} x\). In that case, \(D_b(x,d)\) coincides with the last \(d\) digits of \({}^{y_0+d-d_0} x\) for any positive integer \(d\) greater than or equal to \(d_0\) by the argument for the \(N\) function for base \(b\) above and the induction on \(d\), because \(b^d\) is divisible by the least common divisor of \(\phi(p^d)\) for all prime factors \(p\) of \(b\). Note that the condition on \(d_0\) can be weakened by Carmichael's theorem. |

||

| + | |||

| + | Moreover, under the same assumption of the existence of such a pair \((d_0,y_0)\), we have |

||

| + | \begin{eqnarray*} |

||

| + | & & (D_b(x,d+2) - D_b(x,d+1)) \text{ mod } b^{d+1} = (b^{D_b(x,d+1)} - b^{D_b(x,d)}) \text{ mod } b^{d+1} \\ |

||

| + | & = & (b^{D_b(x,d+1) \text{ mod } b^d} - b^{D_b(x,d)}) \text{ mod } b^{d+1} |

||

| + | \end{eqnarray*} |

||

| + | for any positive integer \(d\) greater than or equal to \(d_0\). Therefore in addition if there exists a positive integer \(d_1\) greater than or equal to \(d_0\) satisfying \(D_b(x,d_1+1) \text{ mod } b^{d_1} = D_b(x,d_1)\), then we obtain \(D_b(x,d+1) \text{ mod } b^d = D_b(x,d)\) for any positive integer \(d\) greater than or equal to \(d_1\) by induction on \(d\). In particular, it implies \(D_b(x,y) \text{ mod } b^d = D_b(x,d)\) for any positive integers \(y\) and \(d\) satisfying \(y_0 \leq y\) and \(d_1 \leq d \leq y\). Thus \(D_b(x,d)\) coincides with the last \(d\) digits of \({}^y x\) for any positive integers \(y\) and \(d\) satisfying \(y_0 \leq y\) and \(d_1 \leq d \leq d_0+y-y_0\). '''Be careful that this argument does not imply that this upperbound \(d_0+y-y_0\) of \(d\) is the best one even if we choose \(d_0\) and \(d_1\) as the least ones.''' |

||

| + | |||

| + | In particular, when \(b = 10\), then the tuple \((d_0,y_0,d_1) = (2,3,2)\) satisfies the conditions. Therefore \(D(d) = D_{10}(3,y)\) coincides with the last \(d\) digits of \({}^y x\) for any positive integer \(d\) greater than or equal to \(2\) and any positive integer \(y\) greater than or equal to \(d+1\). For example, if we present Graham's number as \({}^{y_1} 3\) for a unique positive integer \(y_1\), the last \(d\) digits of Graham's number coincides with \(D(d)\) for any positive integer \(d\) '''greater than or equal to''' \(d_0+y-y_0 = y_1-1\). The last condition was ignored in the wrong belief in this community. Moreover, as we clarified above, '''this argument does not imply that the upperbound \(y_1-1\) of \(d\) is the best one.''' If there exists another tuple \((d_0,y_0,d_1)\) satisfying the conditions and \(y_0 \leq \min \{d_1+1,y_1\}\), then \(D(d)\) coincides with the last \(d\) digits of Graham's number for any positive integer \(d\) smaller than or equal to \(d_0+y_1-y_0\), which is greater than the lowerbound \(y_1-1\). In order to argue on the non-existence of such a tuple \((d_0,y_0,d_1)\), we need to compute the discrete logarithm on base \(x = 3\) or some alternative invariants, although Googology wiki user [[User:Allam948736|Allam948736]] strongly believes that he has succeeded in proving that \(y_1-1\) is the best upperbound of \(d\) by arguments only on \(d\) and \(y\).<ref>[https://googology.wikia.org/index.php?title=Talk%3AGraham%27s_number&diff=277378&oldid=277340 The conjecture by Allam948736]</ref><ref>[https://googology.wikia.org/index.php?title=Graham%27s_number&diff=278051&oldid=274964 The intuitive explanation of why Allam948736 believes that the conjecture has been verified by himself]</ref> Since there is no written proof by him, the non-existence is still an open question. |

||

=== First digits === |

=== First digits === |

||

| − | Computing the first digits of \(^yx\) in a reasonable amount of time for y > 6 is probably impossible. In base 10: |

+ | Computing the first digits of \(^yx\) in a reasonable amount of time for \(y > 6\) and \(x \geq 2\) is probably impossible. In base 10: |

\[a^b = 10^{b \log_{10} a} = 10^{\text{frac}(b \log_{10} a) + \lfloor b \log_{10} a \rfloor} = 10^{\text{frac}(b \log_{10} a)} \times 10^{\lfloor b \log_{10} a \rfloor}\] |

\[a^b = 10^{b \log_{10} a} = 10^{\text{frac}(b \log_{10} a) + \lfloor b \log_{10} a \rfloor} = 10^{\text{frac}(b \log_{10} a)} \times 10^{\lfloor b \log_{10} a \rfloor}\] |

||

| − | The leading digits of \(^ba\) are then \(10^{\text{frac}(^{b - 1}a \log_{10} a)}\), so the problem is finding the fractional part of \(^{b - 1}a \log_{10} a\). This is equivalent to finding arbitrary base-\(a\) digits of \(\log_{10} a\) starting at the \(^{b - 2}a\)th place. The most efficient known way to do this is a {{w|BBP algorithm}}, which, unfortunately, requires linear time to operate and works only with radixes that are powers of 2. We need an algorithm at least as efficient as \(O(\log^*n)\) (where \(\log^*n\) is the {{w|iterated logarithm}}), and it is unlikely that one exists. |

+ | Here \(\lfloor x \rfloor\) denotes the integer part of \(x\), i.e. the greatest integer which is not greater than \(x\), and \(\text{frac}(x)\) denotes the fractional part of \(x\), i.e. \(x - \lfloor x \rfloor \in [0,1)\). The leading digits of \(^ba\) are then \(10^{\text{frac}(^{b - 1}a \log_{10} a)}\), so the problem is finding the fractional part of \(^{b - 1}a \log_{10} a\). This is equivalent to finding arbitrary base-\(a\) digits of \(\log_{10} a\) starting at the \(^{b - 2}a\)th place. The most efficient known way to do this is a {{w|BBP algorithm}}, which, unfortunately, requires linear time to operate and works only with radixes that are powers of 2. We need an algorithm at least as efficient as \(O(\log^*n)\) (where \(\log^*n\) is the {{w|iterated logarithm}}), and it is unlikely that one exists. |

This roadblock ripples through the rest of the hyperoperators. Even if we do find a \(O(\log^*n)\) algorithm, it becomes unworkable at the pentational level. A constant time algorithm is needed, and finding such an algorithm would take a miracle. |

This roadblock ripples through the rest of the hyperoperators. Even if we do find a \(O(\log^*n)\) algorithm, it becomes unworkable at the pentational level. A constant time algorithm is needed, and finding such an algorithm would take a miracle. |

||

| + | |||

| + | Nonetheless, it is still possible to calculate the first digits of \(^yx\) for small values of \(y\). Below are some examples: |

||

| + | |||

| + | [[Binary-Dooqnol|\(^52\)]]: 200352993040684646497907235156... |

||

| + | |||

| + | \(^62\): 212003872880821198488516469166...<ref>https://oeis.org/A241291</ref> |

||

| + | |||

| + | \(^43\): 125801429062749131786039069820...<ref>https://oeis.org/A241292</ref> |

||

| + | |||

| + | [[Tritet Jr.|\(^44\)]]: 236102267145973132068770274977...<ref>https://oeis.org/A241293</ref> |

||

| + | |||

| + | \(^45\): 111102880817999744528617827418...<ref>https://oeis.org/A241294</ref> |

||

| + | |||

| + | \(^49\): 214198329479680561133336437344...<ref>https://oeis.org/A243913</ref> |

||

==Generalization== |

==Generalization== |

||

===For non-integral \(y\)=== |

===For non-integral \(y\)=== |

||

| − | Mathematicians have not agreed on the function's behavior on \(^yx\) where \(y\) is not an integer. In fact, the problem breaks down into a more general issue of the meaning of \(f^t(x)\) for non-integral \(t\). For example, if \(f(x) := x!\), what is \(f^{2.5}(x)\)? {{w|Stephen Wolfram}} was very interested in the problem of continuous tetration because it may reveal the general case of "continuizing" discrete systems. |

+ | Mathematicians have not agreed on the function's behavior on \(^yx\) where \(y\) is not an integer. In fact, the problem breaks down into a more general issue of the meaning of \(f^t(x)\) for non-integral \(t\). For example, if \(f(x) := x\)[[Factorial|\(!\)]], what is \(f^{2.5}(x)\)? {{w|Stephen Wolfram}} was very interested in the problem of continuous tetration because it may reveal the general case of "continuizing" discrete systems. |

Daniel Geisler describes a method for defining \(f^t(x)\) for complex \(t\) where \(f\) is a holomorphic function over \(\mathbb{C}\) using Taylor series. This gives a definition of complex tetration that he calls ''hyperbolic tetration''. |

Daniel Geisler describes a method for defining \(f^t(x)\) for complex \(t\) where \(f\) is a holomorphic function over \(\mathbb{C}\) using Taylor series. This gives a definition of complex tetration that he calls ''hyperbolic tetration''. |

||

| Line 119: | Line 157: | ||

\[^\infty x = \lim_{n\rightarrow\infty}{}^nx\] |

\[^\infty x = \lim_{n\rightarrow\infty}{}^nx\] |

||

| − | If we mark the points on the complex plane at which \(^\infty x\) becomes periodic (as opposed to escaping to infinity), we get an interesting fractal. Daniel Geisler studied this shape extensively, giving names to identifiable features. |

+ | If we mark the points on the complex plane at which \(^\infty x\) becomes periodic (as opposed to escaping to [[infinity]]), we get an interesting fractal. Daniel Geisler studied this shape extensively, giving names to identifiable features. |

| + | ===For ordinals=== |

||

| + | There have been many attempts to extend tetration to [[Ordinal|transfinite ordinals]], including by [[Jonathan Bowers]]<ref>J. Bowers, [http://www.polytope.net/hedrondude/spaces.htm Spaces] (2020)</ref> and [[Sbiis Saibian]]. However, a common problem occurs at \(\omega\uparrow\uparrow(\omega+1)\) because of the successor case \(\omega^{\omega\uparrow\uparrow\omega}=\omega^{\varepsilon_0}=\varepsilon_0\) of the transfinite induction. Bowers's method of passing this problem is also known as the [[climbing method]], but has not been formalised. In other words, Bowers' method is currently ill-defined. |

||

==Examples== |

==Examples== |

||

| Line 130: | Line 170: | ||

* \(^42 = 2^{2^{2^2}} = 2^{2^4} = 2^{16} = 65,536\) |

* \(^42 = 2^{2^{2^2}} = 2^{2^4} = 2^{16} = 65,536\) |

||

*\(^35 = 5^{5^5} \approx 1.9110125979 \cdot 10^{2,184}\) |

*\(^35 = 5^{5^5} \approx 1.9110125979 \cdot 10^{2,184}\) |

||

| − | *\(^52 \approx 2.00352993041 \cdot 10^{19,728}\) |

+ | *\(^52 = 2^{2^{2^{2^2}}} \approx 2.00352993041 \cdot 10^{19,728}\) |

*\(^310 = 10^{10^{10}} = 10^{10,000,000,000}\) |

*\(^310 = 10^{10^{10}} = 10^{10,000,000,000}\) |

||

| − | *\(^43 \approx 10^{10^{10^{1.11}}}\) |

+ | *\(^43 = 3^{3^{3^3}} \approx 10^{10^{10^{1.11}}}\) |

<!-- Don't overdo it, 'k? --> |

<!-- Don't overdo it, 'k? --> |

||

| Line 145: | Line 185: | ||

* The [[Mersenne number|Catalan-Mersenne sequence]] |

* The [[Mersenne number|Catalan-Mersenne sequence]] |

||

| − | * The size of power sets in the von Neumann universe as a function of stage<ref>[http://cp4space.wordpress.com/2013/07/17/von-neumann-universe Von Neumann universe]. ''Complex Projective 4-Space''.</ref> |

+ | * The size of power sets in [[von Neumann universe|the von Neumann universe]] as a function of stage<ref>[http://cp4space.wordpress.com/2013/07/17/von-neumann-universe Von Neumann universe]. ''Complex Projective 4-Space''.</ref> |

* \(f_3\) in the [[fast-growing hierarchy]] |

* \(f_3\) in the [[fast-growing hierarchy]] |

||

== Super root == |

== Super root == |

||

| − | Since <sup> |

+ | Let \(k\) be a positive integer. Since <sup>k</sup>a is well-defined for any non-negative real number a and is a strictly increasing unbounded function, we can define a root inverse function \(sr_k \colon [0,\infty) \to [0,\infty)\) as: |

\(sr_k(n) = x \text{ such that } ^kx = n\) |

\(sr_k(n) = x \text{ such that } ^kx = n\) |

||

| + | |||

=== Numerical evaluation === |

=== Numerical evaluation === |

||

Revision as of 11:06, 30 December 2020

Tetration, also known as hyper4, superpower, superexponentiation, superdegree, powerlog, or power tower,[1] is a binary mathematical operator (that is to say, one with just two inputs), defined as \(^yx = x^{x^{x^{\cdot^{\cdot^{\cdot}}}}}\) with \(y\) copies of \(x\). In other words, tetration is repeated exponentiation. Formally, this is

\[^0x=1\]

\[^{n + 1}x = x^{^nx}\]

where \(n\) is a nonnegative integer.

Tetration is the fourth hyper operator, and the first hyper operator not appearing in mainstream mathematics. When repeated, it is called pentation.

If \(c\) is a non-trivial constant, the function \(a(n) = {}^nc\) grows at a similar rate to \(f_3(n)\) in FGH.

Daniel Geisler has created a website, IteratedFunctions.com (formerly tetration.org), dedicated to the operator and its properties.

Basis

Addition is defined as repeated counting:

\[x + y = x + \underbrace{1 + 1 + \ldots + 1 + 1}_y\]

Multiplication is defined as repeated addition:

\[x \times y = \underbrace{x + x + \ldots + x + x}_y\]

Exponentiation is defined as repeated multiplication:

\[x^y = \underbrace{x \times x \times \ldots \times x \times x}_y\]

Analogously, tetration is defined as repeated exponentiation:

\[^yx = \underbrace{x^{x^{x^{.^{.^.}}}}}_y\]

But since exponentiation is not an associative operator (that is, \(a^{b^{c}}\) is generally not equal to \(\left(a^b\right)^c = a^{bc}\)), we can also group the exponentiation from bottom to top, producing what Robert Munafo calls the hyper4 operator, written \(x_④y\). \(x_④y\) reduces to \(x^{x^{y - 1}}\), which is not as mathematically interesting as the usual tetration. This is equal to \(x \downarrow\downarrow y\) in down-arrow notation.

Notations

Tetration was independently invented by several people, and due to lack of widespread use it has several notations:

- \(^yx\) is pronounced "to-the-\(y\) \(x\)" or "\(x\) tetrated to \(y\)." The notation is due to Rudy Rucker, and is most often used in situations where none of the higher operators are called for.

- Robert Munafo uses \(x^④y\), the hyper4 operator.

- In arrow notation it is \(x \uparrow\uparrow y\), nowadays the most common way to denote tetration.

- In chained arrow notation it is \(x \rightarrow y \rightarrow 2\).

- In BEAF it is \(\{x, y, 2\}\)[2].

- The latter of these also represents tetration in X-Sequence Hyper-Exponential Notation.

- Using Bowers's extended operators, it is \(x\ \{2\}\ y\).

- In Hyper-E notation it is E[x]1#y (alternatively x^1#y).

- In plus notation it is \(x ++++ y\).

- In star notation (as used in the Big Psi project) it is \(x *** y\).[3]

- An exponential stack of n 2's was written as E*(n) by David Moews, the man who held Bignum Bakeoff.

- Harvey Friedman uses \(x^{[y]}\).

Properties

Tetration lacks many of the symmetrical properties of the lower hyper-operators, so it is difficult to manipulate algebraically. However, it does have a few noteworthy properties of its own.

Power identity

It is possible to show that \({^ba}^{^ca} = {^{c + 1}a}^{^{b - 1}a}\):

\[{^ba}^{^ca} = (a^{^{b - 1}a})^{(^ca)} = a^{^{b - 1}a \cdot {}^ca} = a^{^ca \cdot {}^{b - 1}a} = (a^{^ca})^{^{b - 1}a} = {^{c + 1}a}^{^{b - 1}a}\]

For example, \({^42}^{^22} = {^32}^{^32} = 2^{64}\).

Moduli of power towers

Be careful that there were many unsourced (and perhaps wrong) statements on last digits of tetration in this wiki. For example, the last \(d\) digits \(N(y)\) of \(^yx\) in base \(b\) was believed to be computed by the following wrong recursive formula in this community up to December in 2019: \begin{eqnarray*} N(m) = \left\{ \begin{array}{ll} 1 & (m=0) \\ x^{N(m-1)} \mod{b^d} & (m>0) \end{array} \right. \end{eqnarray*} Here, \(s \mod{t}\) denotes the remainder of the division of \(s\) by \(t\). For example, we have the following counterexamples:

- If \(b = 10\) and \(d = 1\), then the formula computes the last 1 digit of \(2 \uparrow \uparrow 4\) in base \(10\) as \(2^{16 \mod{10}} \mod{10} = 2^6 \mod{10} = 64 \mod{10} = 4\), while the last 1 digit of \(2 \uparrow \uparrow 4 = 2^{16} = 65536\) in base \(10\) is \(6\).

- If \(b = 10\) and \(d = 2\), then the formula computes the last 2 digits of \(100 \uparrow \uparrow 2\) in base \(10\) as \(100^{100 \mod{10^2}} \mod{10^2} = 100^0 \mod{10^2} = 1\) (i.e. \(01\)), while the last 2 digits of \(100 \uparrow \uparrow 2 = 100^{100} = 1000 \cdots 000\) in base \(10\) is \(00\).

- If \(b = 15\) and \(d = 1\), then computes the last 1 digit of \(2 \uparrow \uparrow 4\) in base \(15\) as \(2^{16 \mod{15}} \mod{15} = 2^1 \mod{15} = 2\), while the last 1 digit of \(2 \uparrow \uparrow 4 = 65536\) in base \(15\) is \(1\).

The method works when \(x\) is coprime with \(b\) and \(b^d\) is divisible by the least common multiple of \(\phi(p^d) = (p-1)p^{d-1}\) for prime factors \(p\) of \(b\) by Euler's theorem and Chinese remainder theorem, where \(\phi\) denotes Euler function. For example, when \(b = 10\) and \(d \geq 3\), then the condition holds. It is obvious that it does not hold when \(b\) is an odd prime number. Even if \(b\) is not a prime number, the method does not necessarily hold as we have seen the counterexamples \((x,b,d) = (2,10,1)\), where \(b^d = 10\) is not divisible by the least common multiple \(4\) of \(\phi(2^d) = 1\) and \(\phi(5^d) = 4\), and \((x,b,d) = (2,15,1)\), where \(b^d = 15\) is not divisible by the least common multiple \(4\) of \(\phi(3^d) = 2\) and \(\phi(5^d) = 4\). In general, the condition never holds when \(b\) is an odd number.

In particular, the method works when \(x\) is coprime with \(b\) and one of the following holds:

- \(b = 2^h\) for some \(h \geq 1\).

- \(b = 2^h \times 3^i\) for some \(h,i \geq 1\).

- \(b = 2^h \times 5^i\) for some \(h,i \geq 1\), and \(dh \geq 2\).

- \(b = 2^h \times 3^i \times 5^j\) for some \(h,i,j \geq 1\), and \(dh \geq 2\).

- \(b = 2^h \times 3^i \times 7^j\) for some \(h,i,j \geq 1\).

If the method works, then the modular exponentiation can be computed very quickly using several algorithms such as right-to-left binary method. The condition that \(x\) is coprime to \(b\) is important as we have the counterexample \((x,b,d) = (100,10,2)\), although it is often carelessly dropped in this wiki. Further, although it is sometimes believed that the recursive formula works when \(d\) is sufficiently large, \(x = b^d\) is always a counterexample of the recursive formula for any \(b \geq 2\) and \(d \geq 1\) because \(^2 x \mod{b^d} = 0\) and \(x^{x \mod{b^d}} \mod{b^d} = x^0 \mod {b^d} = 1 \mod{b^d} = 1\).

Even if \(x\) is not necessarily coprime with \(b\), the last \(1\) digit \(D_b(x,m)\) of \(x^m\) in base \(b\) for an \(m \in \mathbb{N}\) can be quite easily computed in the case \(b\) is squarefree. First, consider the case where \(b\) is a prime number \(p\). Then \(D_p(x,m)\) is computed in the following recursive way by Fermat's little theorem:

- Denote by \(S_p(m)\) the sum of all digits of \(m\) in base \(p\).

- Then \(D_p(x,m) = D_p(x \mod{p},S_p(m))\).

Since \((S_p^n(m))_{n=0}^{\infty}\) is a decreasing sequences converges to a non-negative integer \(S_p^{\infty}(m)\) smaller than \(p\), the computation of \(D_p(x,m)\) is quickly reduced to the computation of \(D_p(x \mod{p},S_p^{\infty}(m)) \in \{(x \mod{p})^i \mod{p} \mid 0 \leq i < p\}\). Now consider the general case. Then \(D_b(m)\) is computed in the following recursive way by Chinese remainder theorem:

- Denote by \(p_0,\ldots,p_k\) the enumeration of prime factors of \(b\).

- If \(k = 0\), then we have done the computation of \(D_b(x,m) = D_{p_0}(x,m)\) by the algorithm above.

- Suppose \(k > 0\).

- Put \(b' = p_0 \cdots p_{k-1}\). (Since \(b'\) is also squarefree, \(D_{b'}(x,m)\) is also computed in this algorithm by the induction on \(k\).)

- Take an \((s,t) \in \mathbb{Z}^2\) such that \(sb' + tp_k = 1\) by Euclidean algorithm. (Such an \((s,t)\) actually exists because \(b'\) is coprime with \(p_k\))

- Then \(D_b(x,m) = (sb'D_{p_k}(x,m)+tp_kD_{b'}(x,m)) \mod{b}\).

Be careful that this method does not work when \(b\) is not squarefree or the length \(d\) of digits is greater than \(1\), while such restricted methods are often "extended" to general cases just by dropping conditions without theoretic justification in this community as long as people do not know explicit counterexamples, as we have explained above.

For the case where \(b\) is not necessarily squarefree or the length \(d\) of digits is not necessarily equal to \(1\), we need another method to use a shifted system of representatives of \(\mathbb{Z}/b^d \mathbb{Z}\) other than \(\{0,\ldots,b^d-1\}\). Suppose that \(b^d\) is divisible by the least common multiple of \(\phi(p^d)\) for prime factors \(p\) of \(b\). Let \(\mu \in \mathbb{N}\) denote the maximum of multiplicities of prime factors of \(b\). For an \(n \in \mathbb{N}\), we define \(\textrm{Rep}(n) \in \mathbb{N}\) in the following way:

- If \(n < \mu d\), then \(\textrm{Rep}(n) = n\).

- If \(n \geq \mu d\), then \(\textrm{Rep}(n)\) is the unique \(i \in \{\mu d,\mu d + 1,\ldots,\mu d + b^d - 1\}\) such that \((n-i) \mod{b^d} = 0\).

Then even if \(x\) is not necessarily coprime with \(b\), we have \(\textrm{Rep}(x^m) = \textrm{Rep}(x^{\textrm{Rep}(m)})\) unless \(x^{\textrm{Rep}(m)} < \mu d \leq x^m\) by Euler's theorem and Chinese remainder theorem. Now we compute \(\textrm{Rep}(^yx)\). If \(x = 1\), then we have \(\textrm{Rep}(^yx) = 1\). Suppose \(x > 1\). Let \(y_0 \in \mathbb{N}\) denote the least natural number such that \(\mu d \leq {}^{y_0}x\). Then \(\textrm{Rep}(^yx)\) can be computed in the following way:

- If \(y < y_0\), then \(\textrm{Rep}(^yx) = {}^yx\). (Since the right hand side is smaller than \(\mu d\) by the definition of \(y_0\), it is possible to compute the precise value in a reasonable amount of time as long as \(b\) and \(d\) are not so large.)

- If \(y \geq y_0\), then \(\textrm{Rep}(^yx) = \textrm{Rep}(x^{\textrm{Rep}(^{y-1}x)}+b^d)\).

In particular, the last \(d\) digit of \(^yx\) in base \(b\) can be computed as \(\textrm{Rep}(^yx) \mod{b^d}\) because \((^yx - \textrm{Red}(^yx)) \mod{b^d} = 0\).

There was another wrong method to compute the last digits of Graham's number, which was believed to be correct without any reason in this community. Due to the method, for any natural number \(d\), the last \(d\) digits \(D(d)\) of Graham's number in base \(10\) could be computed in the following recursive way: \begin{eqnarray*} D(d) & = & \left\{ \begin{array}{ll} 3 & (d = 0) \\ 3^{N(d-1)} \text{ mod } 10^d & (d > 0) \end{array} \right. \end{eqnarray*} Note that the recursion starts from \(d = 0\), but the result of \(D(0)\) is not meaningful because "the last \(0\) digit" of Graham's number does not make sense. For the obvious reason why this method is wrong, see the main article on Graham's number.

It can be quite easily justified by modifying the upperbound of the length \(d\) of the digits. Let \(b\), \(x\), and \(y\) be positive integers such that \(b\) is coprime to \(x\). We define a natural number \(D_b(x,y)\) in the following recursive way: \begin{eqnarray*} D_b(x,y) & = & \left\{ \begin{array}{ll} x^x \text{ mod } b & (y = 1) \\ x^{D_b(x,y-1)} \text{ mod } b^y & (y > 1) \end{array} \right. \end{eqnarray*} We have \(D_{10}(3,y) = D(y)\) for any positive integer \(y\), and hence this is an extension of the unary \(D\) function above. It is natural to ask when \(D_b(x,d)\) coincides with the last \(d\) digits of \({}^y x\) for positive integers \(d\) and \(y\). The wrong method was based on the wrong assumption that \(D_{10}(3,d)\) coincides with the last \(d\) digits of Graham's number for any positive integer \(d\).

Assume that there exists a pair \((d_0,y_0)\) of positive integers such that for \(b^{d_0}\) is divisible by the least common divisor of \(\phi(p^{d_0+1})\) for all prime factors \(p\) of \(b\) and \(D_b(x,d_0)\) coincides with the last \(d_0\) digits of \({}^{y_0} x\). In that case, \(D_b(x,d)\) coincides with the last \(d\) digits of \({}^{y_0+d-d_0} x\) for any positive integer \(d\) greater than or equal to \(d_0\) by the argument for the \(N\) function for base \(b\) above and the induction on \(d\), because \(b^d\) is divisible by the least common divisor of \(\phi(p^d)\) for all prime factors \(p\) of \(b\). Note that the condition on \(d_0\) can be weakened by Carmichael's theorem.

Moreover, under the same assumption of the existence of such a pair \((d_0,y_0)\), we have \begin{eqnarray*} & & (D_b(x,d+2) - D_b(x,d+1)) \text{ mod } b^{d+1} = (b^{D_b(x,d+1)} - b^{D_b(x,d)}) \text{ mod } b^{d+1} \\ & = & (b^{D_b(x,d+1) \text{ mod } b^d} - b^{D_b(x,d)}) \text{ mod } b^{d+1} \end{eqnarray*} for any positive integer \(d\) greater than or equal to \(d_0\). Therefore in addition if there exists a positive integer \(d_1\) greater than or equal to \(d_0\) satisfying \(D_b(x,d_1+1) \text{ mod } b^{d_1} = D_b(x,d_1)\), then we obtain \(D_b(x,d+1) \text{ mod } b^d = D_b(x,d)\) for any positive integer \(d\) greater than or equal to \(d_1\) by induction on \(d\). In particular, it implies \(D_b(x,y) \text{ mod } b^d = D_b(x,d)\) for any positive integers \(y\) and \(d\) satisfying \(y_0 \leq y\) and \(d_1 \leq d \leq y\). Thus \(D_b(x,d)\) coincides with the last \(d\) digits of \({}^y x\) for any positive integers \(y\) and \(d\) satisfying \(y_0 \leq y\) and \(d_1 \leq d \leq d_0+y-y_0\). Be careful that this argument does not imply that this upperbound \(d_0+y-y_0\) of \(d\) is the best one even if we choose \(d_0\) and \(d_1\) as the least ones.

In particular, when \(b = 10\), then the tuple \((d_0,y_0,d_1) = (2,3,2)\) satisfies the conditions. Therefore \(D(d) = D_{10}(3,y)\) coincides with the last \(d\) digits of \({}^y x\) for any positive integer \(d\) greater than or equal to \(2\) and any positive integer \(y\) greater than or equal to \(d+1\). For example, if we present Graham's number as \({}^{y_1} 3\) for a unique positive integer \(y_1\), the last \(d\) digits of Graham's number coincides with \(D(d)\) for any positive integer \(d\) greater than or equal to \(d_0+y-y_0 = y_1-1\). The last condition was ignored in the wrong belief in this community. Moreover, as we clarified above, this argument does not imply that the upperbound \(y_1-1\) of \(d\) is the best one. If there exists another tuple \((d_0,y_0,d_1)\) satisfying the conditions and \(y_0 \leq \min \{d_1+1,y_1\}\), then \(D(d)\) coincides with the last \(d\) digits of Graham's number for any positive integer \(d\) smaller than or equal to \(d_0+y_1-y_0\), which is greater than the lowerbound \(y_1-1\). In order to argue on the non-existence of such a tuple \((d_0,y_0,d_1)\), we need to compute the discrete logarithm on base \(x = 3\) or some alternative invariants, although Googology wiki user Allam948736 strongly believes that he has succeeded in proving that \(y_1-1\) is the best upperbound of \(d\) by arguments only on \(d\) and \(y\).[4][5] Since there is no written proof by him, the non-existence is still an open question.

First digits

Computing the first digits of \(^yx\) in a reasonable amount of time for \(y > 6\) and \(x \geq 2\) is probably impossible. In base 10:

\[a^b = 10^{b \log_{10} a} = 10^{\text{frac}(b \log_{10} a) + \lfloor b \log_{10} a \rfloor} = 10^{\text{frac}(b \log_{10} a)} \times 10^{\lfloor b \log_{10} a \rfloor}\]

Here \(\lfloor x \rfloor\) denotes the integer part of \(x\), i.e. the greatest integer which is not greater than \(x\), and \(\text{frac}(x)\) denotes the fractional part of \(x\), i.e. \(x - \lfloor x \rfloor \in [0,1)\). The leading digits of \(^ba\) are then \(10^{\text{frac}(^{b - 1}a \log_{10} a)}\), so the problem is finding the fractional part of \(^{b - 1}a \log_{10} a\). This is equivalent to finding arbitrary base-\(a\) digits of \(\log_{10} a\) starting at the \(^{b - 2}a\)th place. The most efficient known way to do this is a BBP algorithm, which, unfortunately, requires linear time to operate and works only with radixes that are powers of 2. We need an algorithm at least as efficient as \(O(\log^*n)\) (where \(\log^*n\) is the iterated logarithm), and it is unlikely that one exists.

This roadblock ripples through the rest of the hyperoperators. Even if we do find a \(O(\log^*n)\) algorithm, it becomes unworkable at the pentational level. A constant time algorithm is needed, and finding such an algorithm would take a miracle.

Nonetheless, it is still possible to calculate the first digits of \(^yx\) for small values of \(y\). Below are some examples:

\(^52\): 200352993040684646497907235156...

\(^62\): 212003872880821198488516469166...[6]

\(^43\): 125801429062749131786039069820...[7]

\(^44\): 236102267145973132068770274977...[8]

\(^45\): 111102880817999744528617827418...[9]

\(^49\): 214198329479680561133336437344...[10]

Generalization

For non-integral \(y\)

Mathematicians have not agreed on the function's behavior on \(^yx\) where \(y\) is not an integer. In fact, the problem breaks down into a more general issue of the meaning of \(f^t(x)\) for non-integral \(t\). For example, if \(f(x) := x\)\(!\), what is \(f^{2.5}(x)\)? Stephen Wolfram was very interested in the problem of continuous tetration because it may reveal the general case of "continuizing" discrete systems.

Daniel Geisler describes a method for defining \(f^t(x)\) for complex \(t\) where \(f\) is a holomorphic function over \(\mathbb{C}\) using Taylor series. This gives a definition of complex tetration that he calls hyperbolic tetration.

As \(y \rightarrow \infty\)

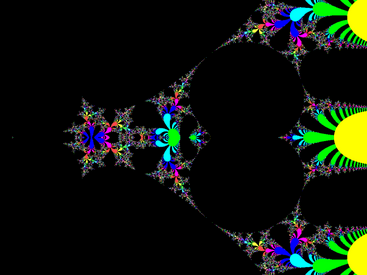

Tetration by escape. Black points are periodic; other points are colored based on how quickly they diverge out of a certain radius, (like the Mandelbrot set).

One function of note is infinite tetration, defined as

\[^\infty x = \lim_{n\rightarrow\infty}{}^nx\]

If we mark the points on the complex plane at which \(^\infty x\) becomes periodic (as opposed to escaping to infinity), we get an interesting fractal. Daniel Geisler studied this shape extensively, giving names to identifiable features.

For ordinals

There have been many attempts to extend tetration to transfinite ordinals, including by Jonathan Bowers[11] and Sbiis Saibian. However, a common problem occurs at \(\omega\uparrow\uparrow(\omega+1)\) because of the successor case \(\omega^{\omega\uparrow\uparrow\omega}=\omega^{\varepsilon_0}=\varepsilon_0\) of the transfinite induction. Bowers's method of passing this problem is also known as the climbing method, but has not been formalised. In other words, Bowers' method is currently ill-defined.

Examples

Here are some small examples of tetration in action:

- \(^22 = 2^2 = 4\)

- \(^32 = 2^{2^2} = 2^4 = 16\)

- \(^23 = 3^3 = 27\)

- \(^33 = 3^{3^3} = 3^{27} =\) \(7,625,597,484,987\)

- \(^42 = 2^{2^{2^2}} = 2^{2^4} = 2^{16} = 65,536\)

- \(^35 = 5^{5^5} \approx 1.9110125979 \cdot 10^{2,184}\)

- \(^52 = 2^{2^{2^{2^2}}} \approx 2.00352993041 \cdot 10^{19,728}\)

- \(^310 = 10^{10^{10}} = 10^{10,000,000,000}\)

- \(^43 = 3^{3^{3^3}} \approx 10^{10^{10^{1.11}}}\)

When given a negative or non-integer base, irrational and complex numbers can occur:

- \(^2{-2} = (-2)^{(-2)} = \frac{1}{(-2)^2} = \frac{1}{4}\)

- \(^3{-2} = (-2)^{(-2)^{(-2)}} = (-2)^{1/4} = \frac{1 + i}{\sqrt[4]{2}}\)

- \(^2(1/2) = (1/2)^{(1/2)} = \sqrt{1/2} = \frac{\sqrt2}{2}\)

- \(^3(1/2) = (1/2)^{(1/2)^{(1/2)}} = (1/2)^{\sqrt{2}/2}\)

Functions whose growth rates are on the level of tetration include:

- The Catalan-Mersenne sequence

- The size of power sets in the von Neumann universe as a function of stage[12]

- \(f_3\) in the fast-growing hierarchy

Super root

Let \(k\) be a positive integer. Since ka is well-defined for any non-negative real number a and is a strictly increasing unbounded function, we can define a root inverse function \(sr_k \colon [0,\infty) \to [0,\infty)\) as:

\(sr_k(n) = x \text{ such that } ^kx = n\)

Numerical evaluation

The second-order super root can be calculated as:

\(\frac{ln(x)}{W(ln(x))}\)

where \(W(n)\) is the Lambert W function.

Formulas for higher-order super roots are unknown.[13]

Pseudocode

Below is an example of pseudocode for tetration.

function tetration(a, b):

result := 1

repeat b times:

result := a to the power of result

return result

Sources

- ↑ Robert Munafo, Beyond Exponents: the hyper4 Operator. Large Numbers.

- ↑ Exploding Array Function

- ↑ bigΨ §2.0.1. Star spangled superpowers

- ↑ The conjecture by Allam948736

- ↑ The intuitive explanation of why Allam948736 believes that the conjecture has been verified by himself

- ↑ https://oeis.org/A241291

- ↑ https://oeis.org/A241292

- ↑ https://oeis.org/A241293

- ↑ https://oeis.org/A241294

- ↑ https://oeis.org/A243913

- ↑ J. Bowers, Spaces (2020)

- ↑ Von Neumann universe. Complex Projective 4-Space.

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tetration#Super-root

See also

Bowers' extensions: expansion · multiexpansion · powerexpansion · expandotetration · explosion (multi/power/tetra) · detonation · pentonation

Saibian's extensions: hexonation · heptonation · octonation · ennonation · deconation

Tiaokhiao's extensions: megotion (multi/power/tetra) · megoexpansion (multi/power/tetra) · megoexplosion · megodetonation · gigotion (expand/explod/deto) · terotion · more...